A preserving jar and the Christ-child - a meditation on the "new creation" for which we prepare and await during Advent

|

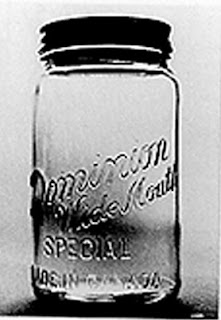

| A Dominion preserving jar |

The substance of this address came about because of one of the great pleasures and privileges of being a minister in Cambridge, namely, the opportunity it provides to engage in long term conversations with many people working at the top of their professions in the arts, the humanities and in the natural sciences.

One such conversation in recent weeks (and continued only yesterday) was had with an eminent British scientist who, throughout his life, has maintained a strong yet intelligent, gentle, flexible and always evolving Christian faith. Since he knows that I have a particular interest in what is called the reception history of the Bible we talked at some length about how the creation stories had been received and interpreted by our Western European culture.

Naturally, for both of us any contemporary reception that understands these stories as literally true, descriptive accounts of the creation is ruled out of court and so he asked me how as a theologian and minister of religion I dealt with this. I said I always tried to make a distinction between the terms "universe" and "world"; I try to use the word "universe" to refer to all the actual material things around us that are explored so well by the natural sciences and I try to use the word "world" only to refer to human domains of meaning. So in common parlance we talk about the worlds of religions and science, as well as the those of politics, finance, jazz, literature, art, film sport and many others.

In short I said that I regarded (or received) the Biblical creation stories as certainly being about the creation, but that this was the creation not of the natural "universe" but, instead, of a human "world." For me these stories mark the creation of an important domain of human meaning in which began an unfolding, creative conversation about what it is to be a human being that continues right up to this very moment. It is, of course, not the only domain of meaning in play for our culture - it never has been - but it is, without doubt, one that came to lie at the very heart of our culture's ongoing conversation about who we are and what life, the universe and everything means.

I like this interpretation because, as we all know, genuine conversations unfold in often unexpected directions and during the course of the best of them wholly new ways of talking about and looking at both the universe and the world can suddenly and unexpectedly show up. When this occurs the conversation doesn’t stop but continues with a wholly new quality, feel and focus about it. We can say, and I do say, that in those moments a "new creation" has occurred. Very occasionally the "new creation" is so powerful that it begins to spread beyond the initial conversation partners into the wider culture and it becomes known to us as a paradigm shift. When a paradigm shift occurs the natural "universe" doesn't change but the way we interpret the universe and understand the meaning of our place in it, most certainly does. In other words a new "world" is created. My scientist friend and I agreed, by the way, that scientific experiments can be understood as being a kind of conversation between ourselves and the universe.

In the world of the natural sciences the two most famous paradigm shifts known to most people are those which moved us from a Ptolemaic cosmology to a Copernican one and from the world view of Newtonian physics to the Einsteinian Relativistic world view.

In the world of religion perhaps the key new conversation, “new creation” or paradigm shift that concerns us - especially at this time of year - is that visible in the gospels and the epistles of the NT. Before them the self-understanding of what it was to be a human-being had been centred on the powerful but fickle heroes and gods of ancient myth - whether Greek, Roman or, of course, our own Germanic and Scandinavian models it matters not. But Christianity brought with it a wholly different focus centred on a person who was not only in themselves weak and powerless and not at all like all previously expected Kings or Messiahs, but someone whose victory in the world was to the heroic mindset shockingly seen in both a pauper’s birth and a criminal’s death on a cross. A strange conception of God and humanity indeed, so strange in fact that St Paul explicitly called it a "new creation" in the two striking verses we explored at the beginning of Advent:

For neither circumcision nor uncircumcision is anything; but a new creation is everything! (Galatians 6:15)

So if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new! (2 Corinthians 5:17)

But to engage in the kind of conversation that has the potential to bring about another “new creation” or paradigm shift we, the participants involved, have to have undertaken a lot of preparatory work - we have to be fluent and thoughtfully creative in the highways and byways of the old conversation, creation or paradigm and both conversation partners need to know well the current domains of meaning they inhabit if they are going to help a new one to show up.

This, by the way, is why we should be exceptionally wary of those in our own time who think that the next step, the "new creation", paradigm or new subject in our conversation in our religious or cultural life will just show up out of nothing and that for this to occur we must abandon or even throw away and destroy our culture’s old stories. We forget at our peril that Jesus' reminder that "every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old" (Matthew 13:52).

Let me now, with the help of Wallace Stevens’ jar, briefly show you how the old world gifts us the new and I’ll then tie this back to the Christmas story. Please note that throughout what follows I only use the word "world" and not "universe."

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion every where.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

Stevens knew that no new creation or new world of meaning comes out of nothing, ex nihilo. A new world comes about when something which is currently in our world but which is, at present, peripheral and insignificant is brought to the centre of our collective attention so that a new world can be gathered by it. It has to be something already in our world and recognisable to us because if that were not the case we wouldn’t be able to see it in the first place and it could have no impact upon us.

Stevens picks as his object a preserving jar - a Dominion jar (and as you will see an important pun is made possible thanks to this name) or, as we would call it here in the UK, a Kilner jar. It’s an instantly recognisable thing and for all its usefulness to us it can hardly be said to be of central, illuminating importance to our culture; it’s very peripheral. Now look at what Stevens does. He brings the jar from the edge of the present world and places it, surprisingly, shockingly even, right in the middle such that it demands our attention. The poem shows how in this act the jar now gathers around it things from the old world in a way such that a new world of meaning shows up - as Stevens says the previously slovenly wilderness is no longer wild and this once peripheral jar now takes dominion everywhere. Importantly, although it is still recognisable to us as something everyday as a jar, as a creator of a new world it takes on a god-like character and can no longer be thought of as quite like anything else in Tennessee - which is to say our world.

It is important to see that the gospel writers’ placing of the Christ-child in the manger and at the centre of our world functioned in very much the same way as did Stevens’ placing of a jar on a hill in Tennessee - year after year we gather together in familes and church communites around the crib. (Click here to see a painting called The Nativity at Night from about 1490 painted by Geertgen tot Sint Jans which encourages the viewer to gather around the crib with the other characters in the Christmas story) It is also vitally important to understand that the point of the Christmas story and Stevens poem may not be precisely either the Christ-child or the jar themselves rather it is that they both help us see something of the work that needs to be done by every generation as it seeks to create a new and better world.

I agree wholeheartedly with the twentieth-century theologian Paul Tillich who said that “If [he] were asked to sum up the Christian message for our time in two words, [he] would say with Paul: It is the message of a "New Creation" (in his sermon called "New Being"). But truly to proclaim this message of hope we need actively to be looking at and engaged with the things our old world currently considers peripheral and marginal and, in conversation together, to allow this "new creation" to come to pass for us in a way relevant to our own times.

When, in two day’s time we awake to greet the Christ-child and gather again around his crib in story, prayer and song all these things must, I think, be borne in mind. We need to see that the new-born baby in the crib is a placeholder for that god-like divine thing which we do not yet recognise but for which we are preparing and waiting for through our hopeful, creative and knowledgeable conversation with each other.

If we do not lose hope and we keep talking with each other then the right Word we are seeking will be made flesh and will bring with it a new creation and a whole new way of being in the world.

Comments

May thanks for your kind and encouraging comment. A happy Christmas to you.