A meditation on the meaning of ‘the best’, ‘second-best’ and of becoming, perhaps, a fox without a hole or a bird without a nest

|

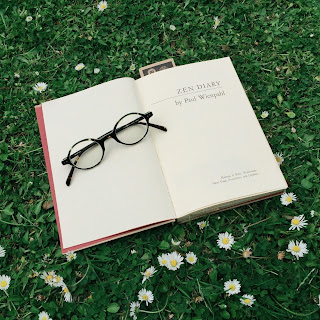

| Paul Wienpahl's "Zen Diary" |

Jesus said:

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like unto treasure hid in a field; the which when a man hath found, he hideth, and for joy thereof goeth and selleth all that he hath, and buyeth that field.

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like unto a merchant man, seeking goodly pearls: Who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had, and bought it.

Matthew 8:19-20 (AV)

And a certain scribe came, and said unto [Jesus], “Master, I will follow thee whithersoever thou goest.” And Jesus saith unto him, “The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head.”

—o0o—

From "Philosophical Reflections" by Paul Wienpahl (Chicago Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, Summer, 1959, pp. 3-18). Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25293511

As I see it, the point is not to identify reality with anything except it self. (Tautologies are, after all, true.) If you wish to persist by ask ing what reality is; that is, what is really, the answer is that it is what you experience it to be. Reality is as you see, hear, feel, taste and smell it, and as you live it. And it is a multifarious thing.

To see this is to be a man without a position. To get out of the mind and into the world, to get beyond language and to the things is to cease to be an idealist or a pragmatist, or an existentialist, or a Christian. I am a man without a position. I do not have the philosophic position that there are no positions or theories or standpoints. (There obviously are.) I am not a skeptic or an agnostic or an atheist. I am simply a man without a position.

That simple sentence, ‘I am a man without a position,’ does not express a philosophy of life. It is not a philosophy at all. It is rather a statement of fact. In it I am simply affirming my own existence. You have to be very careful about it because it is easy to classify and typify. I can be careful about it by taking it simply and directly.

[. . .]

I hate to think that I need a catalyst like my friend. Yet I am afraid that if I go on by myself, I won’t get anywhere. But there’s the nub. Who wants to get anywhere? Why not let myself become what I shall? Trying to become something is trying to be a copy. I guess that we are afraid to become ourselves, and that is why we are seldom original.

This helps me to see that I would rather become a mediocre Paul Wienpahl than a successful type, say a successful college professor. But I am afraid of individuality and, hence, of originality, which is the thing I prize most. No wonder it doesn’t come. I am doing everything I can to prevent it. It is like peace for the world today. And it is the striving for it which would cause me not to recognize it if it did, by a miracle, come. For then it, I, would be like no other thing. And I couldn’t recognize it because of this and because of the striving.

—o0o—

ADDRESS

A meditation on the meaning of ‘the best’, ‘second-best’ and of becoming, perhaps, a fox without a hole or a bird without a nest

Some of you may have heard the brouhaha about the document leaked a couple of weeks ago which revealed that the British Army seemed seriously to have been thinking about dropping from their recruitment campaigns the overarching slogan: “Be the best”.

The story revealed something of the high levels of confusion that exist at the moment within our culture concerning ideas about in what consists an appropriate inclusivity and equality of access in any field or domain of endeavour and what “being the best” might mean.

In an address of 2000 words it is impossible fully to unpack the deep confusion going on here so, at the risk of over-simplifying the matter, let me start simply by pointing out that the only fully inclusive Army, one which which had absolute equality of access, would be (in the terms by which one usually judges armies) deeply rubbish and almost montypythonesque in quality. Leaving aside the always vexed, ethical question of the desirability or not of maintaining expensive standing armies, if you are going to have one then you really do want it to be the best — don’t you? I mean what would be the point of self-consciously striving to have a second-best army?

Anyway, striving to be, and sometimes achieving the aim of being the best (or at least being amongst the best) in this or that domain — whether the army or elsewhere — clearly has a place within every healthy culture. So I want to be clear that, in appropriate contexts, I’m going to continue to champion the value of “trying to be the best.”

However, having said this — and meant it — the drive to “be the best” is not always and in every context a good or healthy thing. In my own life I first began to realise this with regard to poetry and essay writing. As a teenager I wrote lots of both and, in attempting to “learn the trade”, naturally I chose as models writers my teachers and their text books told me were amongst the “the best”.

The trouble was I quickly discovered that, try as I might, I couldn’t, nor wanted to, write poetry like those my culture had defined as the “best”. I also quickly discovered that in the field of essay writing I was no Montaigne, William Hazlitt, Ralph Waldo Emerson or George Orwell. (You are, of course, reading the proof of my assertion right now).

It was, and remains, a disappointing discovery. But I’m nothing if not tenacious, so I consciously decided to start seeking-out and trying to learn from those writers — and later, philosophers — who had been quietly placed by our culture in the categories of second-best or second-rank.

I was helped in my search by the existence of a terrific second-hand bookshop in Bury St Edmunds near where I lived in Suffolk amongst whose dusty volumes of the best one could pick-up many obscure publications by English literature’s so-called “second-best.”

The two writers I discovered who particularly impressed me were Michael Roberts (1902-1948) and Philip Mairet (1886–1975). I imagine that both will be names which mean nothing to you but of course they won’t, because they are only to be found by those who, for whatever reason, decide to become archeologists and dig for treasure in the various fields where a culture’s so-called second-best or second-rank are quietly buried. It’s hugely tempting to talk a bit about Roberts’ and Mairet’s work at this juncture but I’ll resist this because the simple point I want to bring out here is that in discovering them I realiszd I had stumbled upon two pearls of great price and they became for me powerful exemplars of how I might go about becoming myself a writer.

The success I experienced during my late teens and early twenties in discovering these two authors meant that since then I’ve continued actively to explore many other obscure, ignored and forgotten writers, poets, musicians and philosophers and I have to say that search continues regularly to turn up pearls of great price. Aside from Roberts and Mairet, one of my most valuable and influential discoveries in the last ten years was the American philosopher Paul Wienpahl (1916-1980).

Many of you will know that for a long time now I’ve used some of his words (the first two paragraphs of our reading today) to describe my own basic theological and philosophical position as being someone “without a position” by which I mean someone who has stopped trying to articulate any final and fixed theory about the way the world is and my (or your) place in it and who is, instead, simply trying to find a way of acknowledging that one mustn’t identify reality with anything except itself and that reality, i.e. what is really, is as one sees, hears, feels, tastes and smells it, and as one lives it (See Note 1 at the end of this post). And it is a multifarious — and wonderful — thing.

Wienpahl’s point — and mine — is that reality is such that it is always going to resist all attempts at final description (whether poetic and/or scientific) and, therefore, we’d better always be working hard to find good and practical ways to live fully in the world without depending upon the dangerous dream that we will ever achieve absolute dogmatic certainty about and mastery of any domain or, God help us, the world.

Wienpahl’s writing helped me begin to develop a minimalist, religiously naturalistic way of being in the world that could be described as being mystical even as it tends towards (what W. V. Quine described of Henry Bugbee’s thought) as being “an atheistic mysticism, free of mythical trappings.” And, in connection with all this I’ve come wholly to agree with dear old Wittgenstein in thinking that “The mystical is not how the world is, but that it is” (Tractatus logico-philosophicus, 6.44). This primordial mystery — as we talked about together a couple of weeks ago — is one that cannot be got off the table by even the most rabid new-atheist materialist and so we’d better find good, rational ways to acknowledge the known-unknown mystery that surrounds, upholds and commingles with us at every moment of our existence.

However, as Wienpahl notes, by saying one is a person “without a position” one has to be careful because it’s a statement liable to be misunderstood by those rather too eager quickly to “classify and typify” you as holding a dangerously undecided, vacillating, nihilistic philosophy of life. But this would be completely to misunderstand what’s being said here because what Wienpahl (and I) are trying to express by the phrase “being a man without a position” is not “a philosophy of life”, in fact it “is not a philosophy at all. It is rather a statement of fact.”

It’s rather simply to affirm the fact of our own unique, unrepeatable existence — and here’s where a consideration of what is meant by being “best” or “second best” comes back into play.

You will recall from the reading that Wienpahl said he “would rather become a mediocre Paul Wienpahl than a successful type, say a successful college professor” and, along with him, I want to say to you that I would rather become a mediocre Andrew Brown than a successful type, say a successful theologian and minister.

What does he, what do I, mean by this? Well, it’s all compressed into the fourth paragraph of our reading.Wienpahl begins by saying:

“I hate to think that I need a catalyst like my friend. Yet I am afraid that if I go on by myself, I won’t get anywhere.”

Here Wienpahl is acknowledging the strange fact that before one can be authentically whom one is, one always-already needs the help of others. One needs, for example, the help of an already existent world in which there is biology and genetics (and mothers and fathers) that can bring us into being the first place; one needs the help of being born into an existent culture with it’s own languages so as to begin to helps us get to grips with the world around us in the first place; one then needs increasingly able and insightful teachers to help one learn the languages and to see their strengths and weaknesses; then one always needs countless other kinds of help and one will need it ad infinitum. In all this one can most certainly say one needs the catalyst of a friend for without them there could come to be no truly meaningful “I”. But, as Wienpahl quietly acknowledges, at times in our lives acknowledging this can be frightening but, without the catalyst of a friend, we all see at one time or another that we won’t get anywhere at all.

“But”, then, having recognised this, Wienpahl suddenly says,

“But there’s the nub. Who wants to get anywhere? Why not let myself become what I shall? Trying to become something is trying to be a copy.”

What Wienpahl has seen here is the important difference that exists between, on the one hand, seeking to fill certain roles or doing certain jobs in this world that require us closely to follow clear blueprints — say getting to be a soldier — and, on the other hand, seeking to become who we are despite our social “positions” or “roles”.

Trying to become a soldier clearly requires one closely to copy the existing blueprint of “a soldier”; there is here a somewhere, some destination to get to. But trying to become YOU, aside from your role/s in society, is a very different undertaking because there exists no blueprint for you-as-you and so there is no “there” to get to. There never has been someone before who, in every detail, is just like you, and there never will be anyone just like you in the future. In certain respects you may be only marginally different from countless other people but you are different and that tiny difference — potentially anyway — always-already opens-up for you new and modestly original possibilities of being.

It was Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) who perspicaciously noticed that even exactly to copy or repeat something is always to bring about difference. If I am employed endlessly to make widgets according to a strict blueprint, the widget I make on a gloomy, cloudy Monday morning is not the same widget I make under a glorious sunny sky on a Friday afternoon, and I am not the same person making them either.

Oh, to be sure there are plenty of people in the world — priests and ministers of religion often being among the most unpleasant and vociferous of them — who will tell that in God’s mind (or in some other divine or natural plan) there is some pre-existing blueprint of you-as-you to which you must get if you are going to be the “best” you. But I’m here to ask the question “is that really true?”

To me it seems vanishingly unlikely — because, surely, you, me, we all, are men and women (and all gender shades in-between) who underneath it all (even when we don't realize it) are always-already alive, moving freely without a position and always-already able to discover new ways of becoming. Is this, perhaps, what Jesus was talking about when he said “The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head” (Matthew 8:20 AV)?

And, if that’s right, because we have no fixed position, no absolute, final blueprint to follow, no final place to get to (and so no need to get “there”), with regard to us-as-us there can, therefore, be no clear, fixed or final definition of how we should apply to ourselves the words “best” or “second-best”, “first-“ or “second-rank”.

These categories really only come into clear focus where there are actually fixed blueprints which can/must be copied — say when making widgets or being a soldier.

As I have already intimated such fixed blueprints do have their place. If I want widgets then I want the best widget-makers making them; if I want a standing army then I want the best soldiers in it. Perhaps you want neither widgets nor a standing army but there will be plenty of other examples where you do want — and should want — the best.

But, as Wienpahl wrote, perhaps the truth is that we are often afraid to become ourselves, and that is why we are seldom original.

In any case, we must surely all try to take care about how and when we use the phrase, "be the best" (whether addressed to ourselves or others) because it might, or might not, be the genuinely appropriate thing to say. The key thing — or so it seems to me — is always to try to use it so as to help each other, not to become as foxes or birds of the air with their fixed abodes or positions, but to become genuinely free creatures without a fixed abode or position (challengingly called a “home” in Jesus saying) so that we can genuinely be tomorrow what we are not today. Only within this kind of “positionless” living is there to be found the opportunity for genuine repentance, forgiveness, change and transformation to occur.

—o0o—

In saying this I’m not saying that reality is ONLY AS I see, hear, feel, taste and smell it, and as I live it — that is clearly not the case, for reality is obviously way, way more complex and multifarious than any individual’s experience of it. All I'm really trying to do here is push against a radical skepticism which want us wholly to distrust our senses. On this matter I’m very much with Lucretius (and, therefore, Epicurus) in thinking such skepticism is untenable and that we can in fact gain real and meaningful knowledge of the world by relying upon our senses. As Lucretius realised, "not only reason, but our very life is lost "unless we have "the courage and the nerve to trust our senses":

And if your reasoning faculties can find

No explanation why a thing looks square

When seen close up, and round when farther off,

Even so, it might be better for a man

who lacks the power of reason, to give out

Some idiotic theory, than to drop

All hold of basic principles, break down

Every foundation, tear apart the frame

That holds our lives, our welfare. All is lost,

Not only reason, but our very life,

Unless we have the courage and the nerve

To trust the senses, to avoid those sheer

Downfalls into the pits and tarns of nonsense.

All that verbose harangue against the senses

Is utter absolute nothing.

If a building

Were planned by someone with a crooked ruler

Or an inaccurate square, or spirit-level

A little out of true, the edifice,

In consequence, would be a frightful mess,

Warped, wobbly, wish-wash, weak and wavering,

Waiting a welter of complete collapse—

So let your rule of reason never be

Distorted by the fallacies of sense

Lest all your logic prove a road to ruin.

Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, Book IV, line 500 ff. (trans. by Rolfe Humphries, Indiana University Press, 1968, p. 133)

Comments